Chronic Diseases

Feb 8, 2024

The story of Aditya Suresh, a young man who tragically lost his father to a sudden heart attack, serves as a stark reminder of a hidden health crisis facing the South Asian community. Despite often appearing healthy, individuals of South Asian descent, including those from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal, have a fourfold higher risk of developing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) compared to the general population. This vulnerability manifests as earlier onset, often striking before the fifth decade of life, highlighting the urgent need for awareness and action.

A Startling Reality

Aditya's story is not an isolated incident. South Asians, encompassing individuals from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and neighboring countries, face a fourfold higher risk of ASCVD compared to the general population. What's more alarming is the onset of heart disease occurring up to a decade earlier, often before the age of 50.

A Global Crisis

While South Asians represent a quarter of the world's population, they account for a staggering 60% of global heart disease cases. The mortality rates due to coronary heart disease have seen exponential rises, particularly in developing countries, sounding the alarm for a looming public health crisis.

Unveiling the Concealed

Despite the substantial population of South Asians in the United States, their cardiovascular health risks remained obscured due to the lack of disaggregated data. Recent studies have shed light on the heightened vulnerability of South Asians, distinct from other Asian ethnicities, emphasizing the urgent need for targeted interventions.

The MASALA Study

The groundbreaking MASALA study, examining a cohort of over a thousand South Asians living in America, underscores the gravity of the situation. Not only do South Asians exhibit distinct cardiovascular characteristics, but they also face poorer outcomes post-cardiac interventions compared to their Caucasian counterparts.

Diabetes: A Double Jeopardy

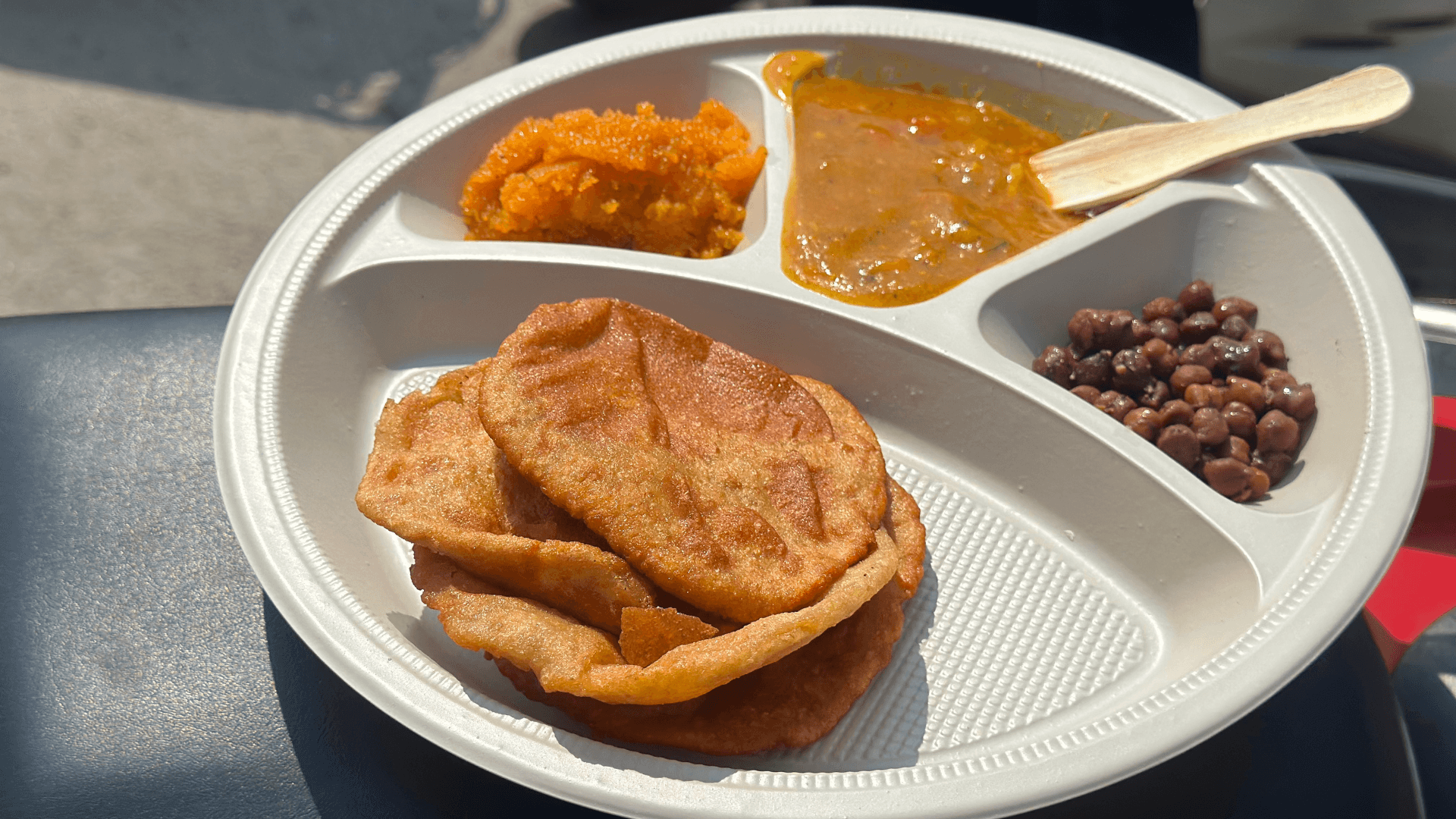

The predilection for impaired glucose tolerance among South Asians translates into a twofold higher incidence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) compared to Caucasians. The dietary transition from traditional South Asian fare to a Westernized diet rich in saturated fats and refined carbohydrates exacerbates this risk.

Beyond Genetics

While genetics play a role in this increased risk, several other factors contribute to the high prevalence of ASCVD in South Asians:

Metabolic Syndrome: South Asians are more prone to developing metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions including abdominal obesity, high blood pressure, high blood sugar, and abnormal cholesterol levels. This combination significantly increases the risk of heart disease and stroke.

Dietary Shifts: The traditional South Asian diet, rich in carbohydrates, saturated fats, and limited in fruits, vegetables, and lean protein, can contribute to weight gain, unhealthy cholesterol levels, and insulin resistance. The integration of the Western diet with its abundance of processed foods and sugary drinks further exacerbates these risks.

Socioeconomic Factors: Lower socioeconomic status, often linked to limited access to quality healthcare, healthy food options, and stress management resources, can disproportionately impact South Asian communities, perpetuating a cycle of poor health outcomes.

Lack of Awareness: Culturally ingrained beliefs and a tendency to prioritize family needs over personal health can sometimes lead to delayed diagnosis and management of heart disease risk factors. This lack of awareness can have detrimental consequences.

Examples from Daily Life:

To illustrate these factors, consider the following scenarios:

Mr. Patel: A 50-year-old businessman enjoys traditional South Asian meals with rice, lentils, and ghee but rarely incorporates vegetables into his diet. He leads a sedentary lifestyle due to long work hours and experiences mild stress due to financial pressures. These factors contribute to his elevated blood sugar and cholesterol levels, putting him at increased risk for ASCVD.

Ms. Kaur: A young professional, Ms. Kaur juggles work and family commitments, often resorting to convenient processed foods and sugary drinks due to time constraints. This dietary pattern, coupled with limited physical activity, increases her risk of developing metabolic syndrome and its associated cardiovascular complications.

Empowering Our Community:

The good news is that ASCVD is largely preventable through lifestyle modifications. Here are some actionable steps South Asians can take to protect their hearts:

Embrace a Heart-Healthy Diet: Reduce refined carbohydrates, saturated fats, and added sugars. Prioritize fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean protein sources. Explore healthier versions of traditional dishes.

Move Your Body: Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise per week. Find activities you enjoy, such as brisk walking, dancing, or swimming.

Manage Stress: Practice relaxation techniques like yoga, meditation, or deep breathing exercises to manage stress effectively.

Regular Checkups: Schedule regular checkups with your doctor to monitor blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels. Discuss your family history and risk factors with your healthcare provider.

Community Engagement: Participate in community programs and support groups focused on promoting healthy lifestyles and raising awareness about ASCVD in South Asians.

A Collective Effort:

Combating this public health challenge requires a multifaceted approach:

Healthcare Professionals: Culturally competent healthcare providers can play a crucial role in early identification, risk assessment, and culturally tailored management of ASCVD risk factors in South Asian patients.

Policymakers: Implementing policies that promote access to healthy food options, physical activity opportunities, and culturally appropriate healthcare services can significantly impact the South Asian community's health outcomes.

Community Leaders: Raising awareness through educational campaigns, community events, and partnerships with healthcare providers can empower South Asians to take charge of their health and well-being.

A Call to Action

Aditya's poignant narrative highlights the imperative for early intervention and heightened awareness within the South Asian community. Through lifestyle modifications and proactive healthcare measures, the trajectory of cardiovascular diseases can be altered, sparing families from the devastation wrought by preventable tragedies.

Learning from Loss

Aditya's resolve to honor his father's memory by prioritizing his health serves as a beacon of hope amid adversity.

By acknowledging the unique challenges faced by South Asians, taking individual responsibility, and fostering a collaborative effort, we can create a future where heart health is not a looming threat but a lived reality for all.